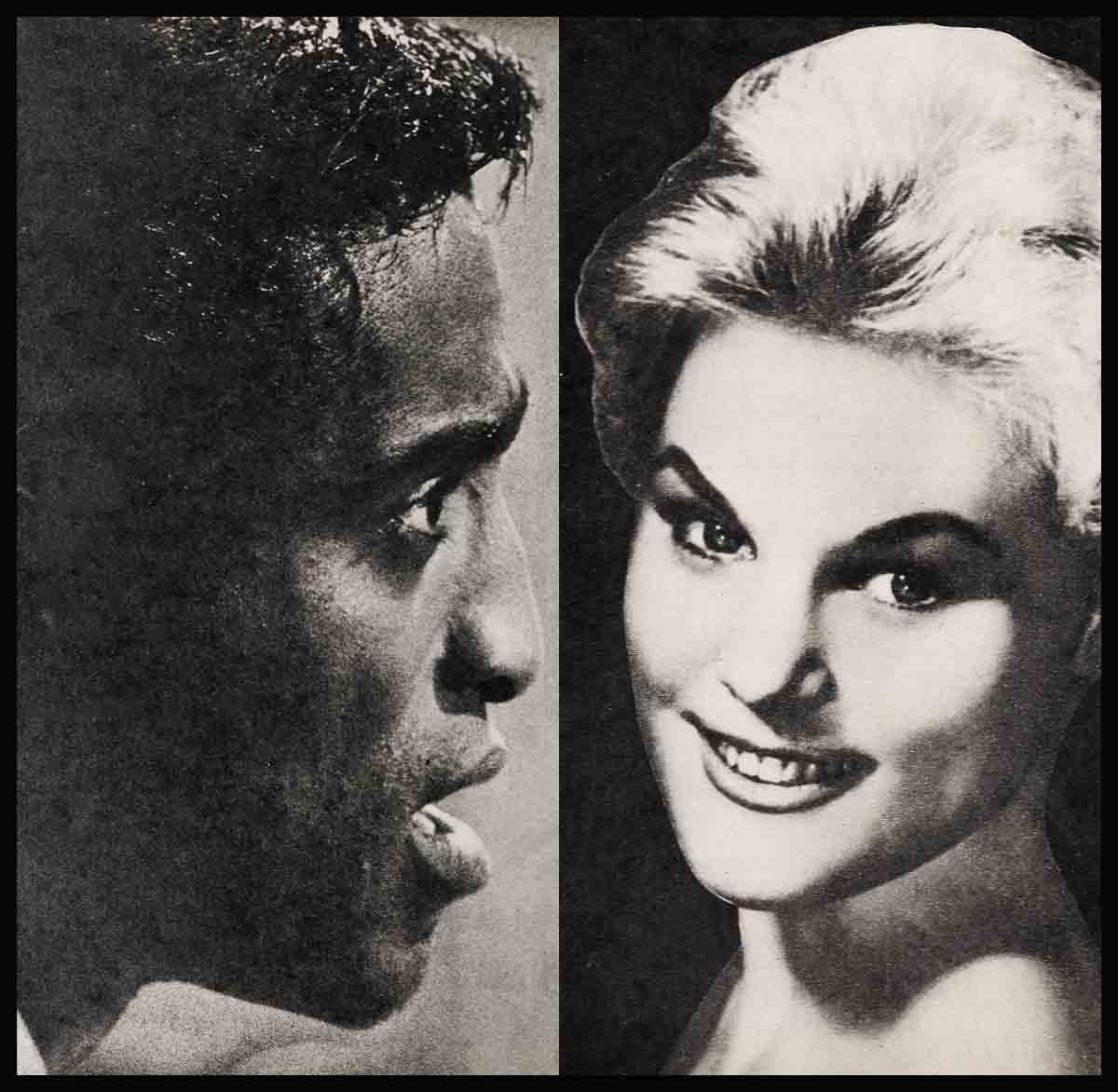

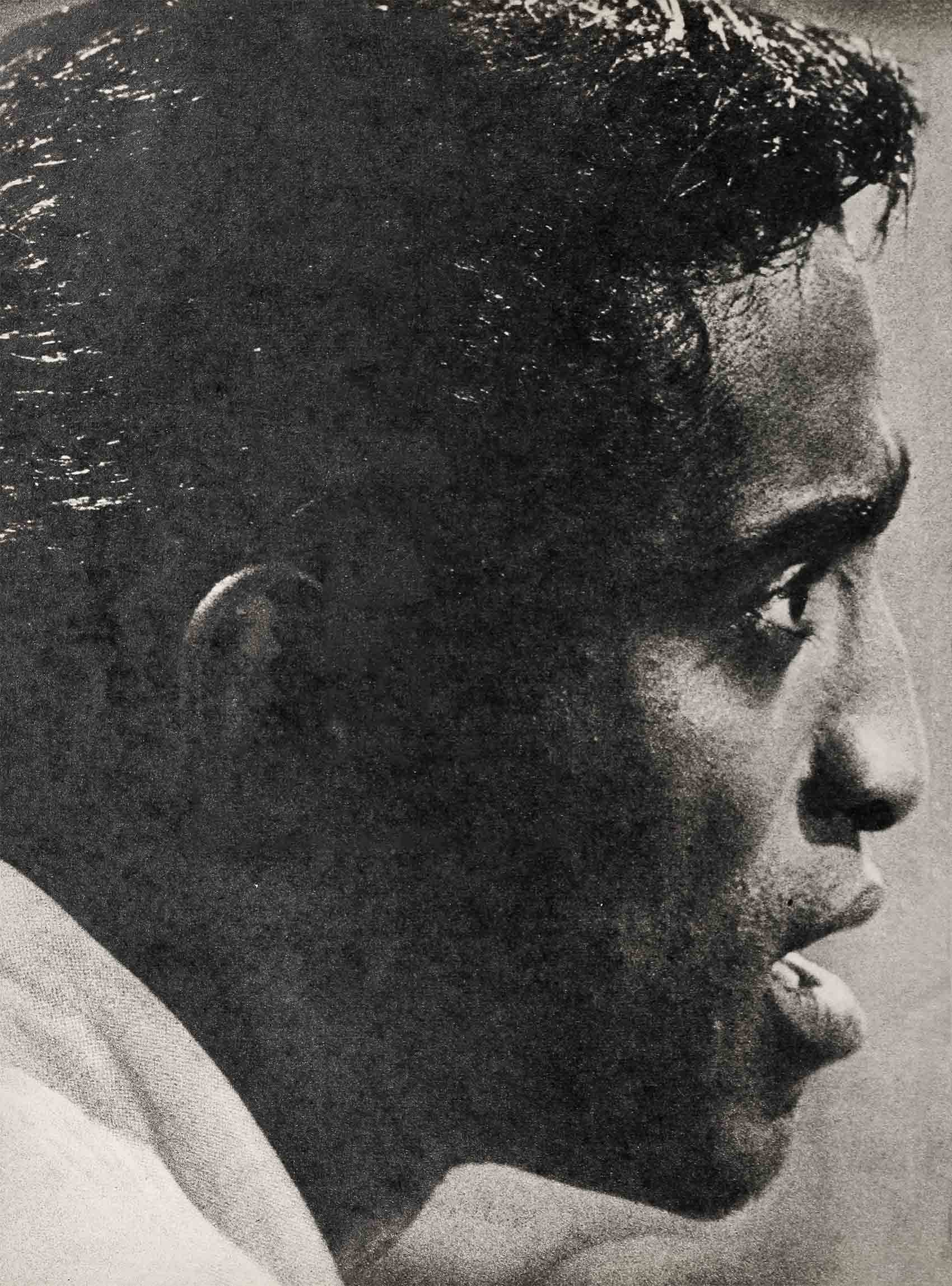

We Have A Right To Be Married—Sammy Davis, Jr. & Joan Stuart

Sammy Davis Jr.’s heart wasn’t in this cocktail party. He was tired if after the long trip from Hollywood to Montreal, tired just thinking about his opening tomorrow night at the Bel Vue Casino, here in the French-Canadian city.

He shook hands with most of the hundred-or-so guests. He laughed at their jokes. Because it was expected of him, he told some jokes of his own.

“I’ve got to get out of here and grab some shuteye,” he told one of his managers, “or I’m just gonna sit down in that chair over there and this town’s gonna know me as Sleepin’ Sam.”

“Sure, sure, Sammy,” the manager said, laughing and taking his arm and leading him through the crowd, to a corner Way across the room. “But these kids, they’re dying to say hello. Show kids, from some club down the street. And just a few minutes, just a few words—it means so much to them, you know Sammy.”

Sammy saw her at that moment, even before he reached the corner where she stood with others. She looked familiar, this loveliest-looking of girls—tall, pale blonde, green-eyed.

Instinctively, Sammy smiled at her. And she smiled back.

Of the group, she was the last to introduce herself.

“I’m Joan Stuart,” she said, when her turn came.

“Hi,” Sammy said, shaking her hand.

“Ahem,” she said, embarrassed, when he failed to let it go.

Sammy laughed nervously, jerking his hand back to his side. “Excuse the old worn-out line,” he said, “but haven’t we met before?”

Joan nodded. “Sort of, in Toronto, a few months ago,” she said, “at CBC—when you did your television show. I was doing a show, too. My parents came to visit me one day. We passed you in the hall and said hello.”

“Well!” Sammy said, laughing nervously again, and then turning back to the others.

For the next ten minutes, excitedly, the others asked him all sorts of questions; about himself, show business in America, Hollywood, Vegas, about friends of his like Sinatra, Dean Martin, Tony Curtis.

And then, suddenly, a waiter sang out “Last call for drinks!”—and they excused themselves and were gone.

“Some friends you’ve got,” Sammy said, lightly, smiling, turning again to Joan Stuart, the only one of the group who’d remained behind. “Very polite, I mean.”

“They’re just excited,” Joan said. “It isn’t often we get invited to parties like this, with big celebrities, fancy canapés, drinks, everything. It’s a little hard knowing where to turn first.”

Strangely uneasy

“How come you didn’t go with them?” Sammy asked.

“I’ve had a drink,” said Joan. “I have two shows to do tonight. enough for me.”

“You sing? Dance?” Sammy asked.

“Dance,” Joan said. “Right now I’m working a club down the street.”

“I’d like to come and see you some night,” Sammy said.

“Would you?” Joan asked.

Sammy reached into his pocket for a cigarette. He was feeling strangely uneasy. “Sure,” he said, “you just name the night.”

His manager came over to them now, before Joan had a chance to speak again.

“Sammy,” said the manager, whispering hoarsely, “the people who’re throwing this blast, they want you to go to dinner with them tonight. D’ve been telling them how pooped you are, but they won’t listen. Will you go over and tell them yourself—please?”

Sammy lit his cigarette, briskly.

“Pooped?” he asked. “Who’s pooped?”

His manager looked at him, stunned. “Well, it ain’t me who’s been doing the complaining,” he said. “You’re the guy who was just—”

“Listen,” Sammy said, cutting in. “I’ve got a great idea. If it’s dinner we’ve got to have, why don’t we have it at the—” He looked over at Joan. ‘“Where’d you say you worked?”

“The Chez André,” Joan said.

“Chez André, that’s it,” Sammy said. “We can watch Miss Stuart’s show first,” he went on, “and then, if it’s all right with Miss Stuart, she can join us for dinner after the show . . . Is that all right with you, Miss Stuart? Joan?”

She hesitated a moment.

Then she nodded.

“See,” Sammy said to his confused manager, “it’s all settled. Now go tell the people. . . .”

After dinner that night, Joan did a second show and then went with Sammy and the rest of the small party to a coffee house not far from the club.

Sammy remembers

“We sat next to each other,” Sammy remembers, “and we talked. We felt close to each other right from the beginning. Joan told me about herself. She was twenty-one, from Toronto. Her folks were conservative people, who didn’t want her to enter showbusiness, but who gave in after a while, after they saw how much she loved dancing, how it meant practically everything to her. She’d led a pretty sheltered life, she said. She hadn’t gone out on dates much, she hadn’t ever had a real boyfriend. When she was fifteen, the age most other girls start going out with boys, Joan was beginning to dance with the Canadian Ballet. This was a rugged life, a strict life, with little time for having fun. Now that Joan was out of the ballet and doing club work, she had more time to herself, she said. And she spent most of her free time reading, or taking long walks up and down streets she’d never walked before, or going to a park and sitting and watching the other people there, the kids mostly. She loved kids, she said.

“Me, when I began to talk to Joan, I felt like a different person. I found that this was the first time I ever sat with a girl and was myself—talking about myself as I really am, not as Sammy Davis Jr., nightclub star. I was serious. For once, with this girl, I felt I could let go of the clown face I’ve had to wear all the time, the clown face people always expect me to wear. I didn’t have to be flip and cute. Boy, it was a wonderful feeling, me talking to her, her talking to me. Once we got started, we didn’t seem to ever want to stop.”

It was dawn when he and Joan finally did stop.

They looked around.

The others had all gone.

The place was empty except for themselves and a doorman, who sat snoozing on a chair near the entranceway.

“Hey,” Sammy said, “what time is it, anyway?”

Joan looked down at her watch. “A quarter after six,” she said.

“What do you say we go grab some breakfast?” Sammy asked.

“Oh no,” Joan said. “You open in a show tonight, remember? You’re tired, Sammy, and you need some sleep.”

“Awwwww,” he started.

“Don’t be a little boy now,” Joan said, gently. “Tonight’s a big night for you. An opening. Tonight’s important.”

“Tonight’s important,” Sammy said, quickly, “only if I know I’m gonna be seeing you again.”

“I’d like to see you again, Sammy,” Joan said. “This was fun, such fun.”

“Better than your books, your walks, your parks?” Sammy asked, winking.

“A little,” said Joan, winking back.

They got up, and held hands, and left the place.

And as they did the doorman, still sitting in his chair, opened one eye, watched them. and shook his head. . . .

How can one man be so lucky?

They met that night. And the day and night after. And the day and night after that. They had a great time together, a fabulous time. They drove out to the country. They saw the famous sights of the city. They went searching for out-of-the-way restaurants in the Old French Town. They took a river boat-ride down the St. Lawrence. They climbed to the top of the Hill, and looked down at the city, the river, the fields beyond. And all the time they talked and were together, and got to know each other more and more. . .

The fifth night was different somehow, right from the beginning. Joan, walking with Sammy down Victoria Street, away from her club, noticed that he was quiet. unusually quiet, that he seemed to be worried about something.

“How’d your show go, Sammy?” she asked, after a while.

“Not too hot,” he said.

“Are you feeling a little sick?” Joan asked.

“No,” Sammy said.

“Then what was wrong?” Joan asked.

“I had something on my mind,” Sammy said.

“What?” she asked.

“Never mind,” he said.

“Please, Sammy, won’t you tell me what?” Joan asked.

“I said never mind!”

The words came like a slap. Joan stopped walking and faced him.

“If you’d rather not go anywhere, I can take a cab and go home,” she said.

Sammy took a deep breath. “Look, Joan,” he said, his voice softer, “what I was thinking during the show, all during the show—it was funny.”

“Funny?” she asked.

“I mean you’d laugh at me if you knew what I was thinking,” Sammy said. “See?”

“No,” Joan said, “I don’t see.”

“I mean,” Sammy said, “you’d laugh if you knew I was thinking about you and me, about us being married, about you being my wife.”

“Why would I laugh?” Joan asked.

Sammy took her hand. He held it hard.

“Hey,” he said, “hey . . . hey . . . this is all backwards, all cockeyed backwards.” Again, he breathed in deeply. “Let me start from the beginning,” he said. He shrugged. “I love you, Joan, and I want to marry you,” he said.

“I want to marry you, Sammy,” she said. She brought her free hand up to his cheek, and held it there. “I love you more than anything in life. I feel good when I’m with you. I’m alive when I’m with you. Alive and happy, like I’ve never felt before . . . Last night, Sammy, after I left you, I went to bed and prayed for only one thing. That the night would go quickly and that morning would come, so I could see you again . . . Oh Sammy, I love you so much. So much.”

“My God,” he said, throwing back his head, looking up, “how can one man on this here earth be as lucky as I am?”

He laughed now and grabbed Joan and kissed her.

And then, after the kiss, he took her hand and they began to walk again.

Problems bigger than most

“We must have walked a couple of hours,” he remembers. “There were so many things to talk about. Real things. Problems. I told Joan it wasn’t going to be any bed of roses for us, a colored man married to a white girl. She said she knew that. I told her there were going to be lots of uncomfortable moments in her life from now on, that she was going to get a lot of criticism and ridicule and dirty looks, lose a lot of her friends. She said she knew that, too, and didn’t care.

“Besides the color problem, there was the difference in our religions: Joan is Catholic, I’m a Jew. I became a convert several years ago. We talked about that, about how strongly I felt about being Jewish, and Joan said that while she would not change her faith she would have our children raised as Jews.

“I remember Joan saying, ‘These problems, Sammy—they’re bigger than most people’s, yes. But we can lick them, Sammy. Love can lick anything. And that’s what we’ve got, to start with, to last us through the rest of our lives . . . Love.’ ”

They walked on, holding hands, talking.

Till, at one point, they came to an all-night drugstore and Sammy said, “You know what I’m going to do, honey? I’m going to phone my Mom, in Hollywood, and tell her the news.”

They went into the drugstore, and Joan waited outside the phone booth while Sammy called.

He was all smiles when he came out.

“What did she say?” Joan asked.

“She said: ‘She must be very nice, Sammy, for you to want to marry her in spite of what the consequences might be,’ ” Sammy told Joan. “Then she said: ‘I’m glad for you, son. You’re thirty-four years old. You’ve worked hard all your life, since you were five years old. It’s about time you started getting some personal happiness out of this life.’ ”

Joan smiled, too, now.

“She sounds like a beautiful woman,” she said.

“Mom?” Sammy asked. “You’ll be crazy about her. Just wait till you meet her.”

He paused.

“Joannie,” he said then, “about your parents—are you going to call them, tell them?”

He watched the smile begin to disappear, slowly, from her face.

“Of course,” she said.

“Now?” Sammy asked.

Joan shook her head. “No, not right now, she said. “It’s . . . It’s after one already. They’re probably fast asleep. I’d hate to get them up. My father, especially, he’s such a sound sleeper and—”

Sammy laughed and interrupted her.

“So you’ll call them tomorrow,” he said, “same thing.” He pointed to a counter, on the other side of the drugstore. “Come on, let’s have a cup of hot coffee for now, huh?” he asked.

Joan followed him, but didn’t answer this time. She seemed, suddenly, to be thinking about something else. . . .

“We have a right . . .”

It was 6:00 p.m. the following day. Joan was in her room, alone. She sat staring at the telephone beside her. She’d been sitting this way for more than an hour now, staring at the phone, wanting to pick it up, not picking it up.

Finally she brought her hand over to the receiver, and lifted it and dialed.

She heard her mother’s voice a few seconds later:

“Joan, how are you, darling? It’s been days since you’ve called. Is everything all right?”

Joan said she was fine; that yes, everything was all right.

For the next minute or so she asked about her father—how was he; had he got home from work yet?

“Just now, he got in this second,” her mother said.

“Mother,” Joan said, suddenly, urgently.

“Yes?” her mother asked.

“I’m getting married,” Joan said.

“You’re—” Her mother stopped and began to laugh. “Joan. How wonderful. What a wonderful surprise. When did all this happen? Who, who’s the man?”

“You met him once, mother, at CBC, a few months ago,” Joan said. “The day you came to visit the studio.”

“That nice director?” her mother asked, “The one from Winnipeg with the deep blue eyes? Him, Joan?”

“No,” Joan said. “His name is Sammy Davis. He’s an entertainer. Sammy Davis, Jr.”

There was a long, a very long, pause.

“Joan,” her mother said, finally, a tremor in her voice, “are you talking about the American—the colored singer?”

“Yes,” Joan said.

“And you’re what?” her mother asked. “—You’re going to marry him?”

“I love him, Mother,” Joan said. “And yes, I’m going to marry him.”

“Is this a joke, Joan Stuart—is this your idea of something funny, calling me up and telling me something like this?”

“Mother—” Joan started to say.

“Is this something you’re doing for publicity?” her mother shouted. “Did one of those agents get you into this, for publicity, for some disgusting publicity?”

“Mother,” Joan said, “I just want you to know, no matter what you feel right now, that I am deeply in love with this man and that I want to marry him. I’d like your approval, yours and Dad’s. Your blessings. But—”

Again her mother cut in. “Approval? Blessings?” she asked. Her voice rose. “Are you serious? Are you—”

Joan heard her mother scream, suddenly, and call for her father. She heard her repeat some of the facts she had just told her—“Sammy Davis,” she heard her say, “Negro . . . our baby . . . marry . . . Negro . . . Negro . . . Negro!”

Finally, she heard her dad’s voice.

“Joannie,” she heard him say, “you’re twenty-one now, on your own. You make your own decisions. But just let me tell you this: I’ve raised you, daughter, and I know you’re a good girl. Just take your time. And don’t do anything foolish.”

“Dad,” Joan said, “I know exactly what I’m doing. Believe me. Please believe me . . . You’re right, Dad. I amtwenty-one. I am on my own now. I do have to make decisions for myself. And this is my decision. Sammy and I—we have a right to be married. We—”

Now she began to cry.

“Joan, Joanie,” she heard her father’s voice say.

She tried to answer, to talk.

But she couldn’t.

Before she knew it, she had hung up.

She rose from her chair, and walked across the room, to a window there. She looked down at the street below, at the stream of people walking by.

“Please, please,” she found herself sobbing, “give us a chance. Won’t you?”

There was a knock on the door then.

It opened, and Sammy walked in.

He knew immediately what had happened.

“You called your folks?” he asked.

“Yes,” said Joan.

“They don’t want it, us, together, married?” Sammy asked.

Joan shook her head.

Sammy walked to a chair and sat. He looked at Joan, near the window, crying.

“Joannie,” he said, after a while, softly, “maybe this is for the best. Maybe it’s good you learn now, from your own family, what part of your future would be like.”

He paused.

Joan said nothing.

“Maybe it’s best you find out now, at the beginning,” he went on then, “—in time for you to change your mind.”

“I can’t say I won’t mind, Joannie,” he said, “but—”

“Don’t, Sammy, don’t,” Joan shouted, suddenly. “Don’t talk like that . . . Don’t you start talking like that now. Or else I’ll die. Right here, on this spot, I’ll wither up and die . . . I love you, Sammy. I love you.”

“And you still want to marry me?” he asked.

Joan ran from the window, and threw herself in his arms.

This was her answer—her final, never-ending answer.

THE END

Sammy starred in PORGY AND BESS, Columbia, and will be seen in OCEANS 11, Warner Bros.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1960

No Comments